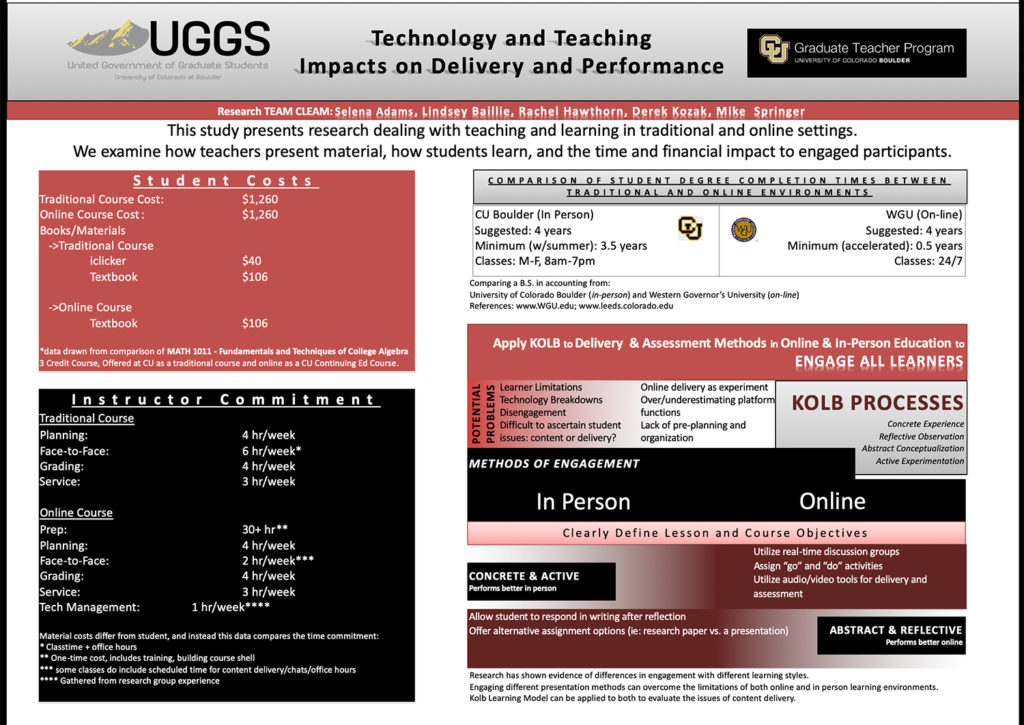

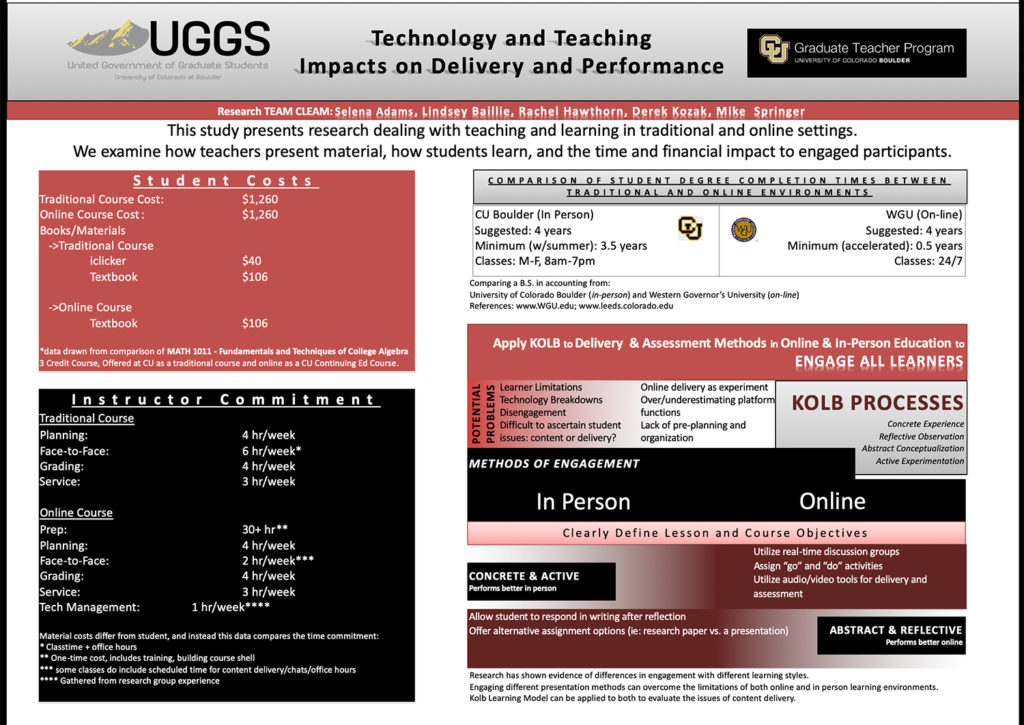

Research poster presentation comparing online to in person education. Part of a group research project with the Graduate Teacher Program at University of Colorado Boulder. 2013

I Do Stuff, I Like Things, & I Have Thoughts

Research poster presentation comparing online to in person education. Part of a group research project with the Graduate Teacher Program at University of Colorado Boulder. 2013

This writing sample is from my 2012 comprehensive exams.

Q3. Discuss the impact of critical theory on art history and criticism, specifically within the frame of the journal October. Include discussion of the trajectory of the journal, and the handling of the Frankfurt School and related topics within the journal’s publishing history. Also address the legacy of the October group through journals such as Grey Room and Nonsite.org.

Critical Theory, as a concept, can be considered to have had a relationship with Art History from its early beginnings. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer wrote about aesthetics in their book on the Culture Industry, The Dialectic of Enlightenment. When looked at in the reverse, however, there is also an influence. Meyer Schapiro, one of the major art historians of the 20th century, was a close friend and associate of Adorno and other members of the Frankfurt school. His consideration of issues such as class, Marxist thought, and other social topics played a major role in the development of Schapiro’s art historical approach.

The term “critical theory” in itself has multiple meanings, which can both be read as affective approaches regarding art history. Primarily, and for the purposes of this paper, Critical Theory (capitalized) refers to the writings and theoretical considerations of the unified group of philosophers known as The Frankfurt School. The Frankfurt School developed out of the Institute for Social Research in 1929-1930, and includes names like Horkheimer, Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Jürgen Habermas, among others. The “critical” theory of the Frankfurt School is considered to have a specific concern that separates it from traditional philosophical approaches, in that it specifically seeks to illuminate issues of human emancipation, and integrate the philosophical approach with those of the natural and social sciences. One can identify any theoretical or philosophical approach with the same general intent as belonging to the larger context of critical theory (not capitalized), including concerns such as feminism, race, class and post-colonial studies.

The major theorists of the loose and informal association called “The Frankfurt School” fled to the United States as a result of the advancement of the National Socialist party in Germany, when the environment became inhospitable to Jews and intellectuals. It was during the exile of Adorno and others that the initial development of The Dialectic of Enlightenment began. Schapiro’s “unorthodox Marxism” was also developed during this time through his associations with Adorno and others. Schapiro’s approach has been, at times, criticized for radicalism, but his awareness and openness to social theories and philosophies such as those addressed b the Frankfurt School paved the way for art historians later on to consider the application of Critical Theory to their work. Combined with the social changes that happened across Europe, including the student uprisings in Paris in 1968, and the race riots and explosion of feminist and racial concerns on campuses in the United States, the publication of The Dialectic of Enlightenment in English in 1972 set the stage for art historians to address critical theory in a more direct manner, and nowhere has this engagement been more consistent than in the pages of October, a journal published by MIT press, started by Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson in 1976.

To begin with, it helps to examine the particulars of the major players of the October group, and how their considerations have shaped the journal, and the later iterations of theoretical writings developed by the next generation of critical theorists, through journals such as Grey Room (also published by MIT press) and Nonsite, an online quarterly journal of art and theory.

New York art critics Michelson and Krauss left the editorial staff of Artforum magazine to begin October. The journal presents itself as being “at the forefront of contemporary art criticism and theory,” an approach which has aligned itself with leftist social views. Despite this, Krauss and the magazine still retain a connection to the 1960s era of art criticism as developed by Clement Greenberg, most particularly within the realm of formal analysis.

Krauss, through her teaching and publishing, as well as her tenure at October, has focused on the development of modern art, including concerns about the indexicality of images, the archive, and medium specificity – a term which, to read Krauss, becomes more clearly distinct from materiality. Essays such as “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” and “Line as Language” address the idea of displacement as part of the specificity of sculpture, while her later writings focus on the index as particular to the medium of photography. Through her work as a founding editor at October, Krauss has helped to frame art criticism and theory in America within the larger international discussion of politics and aesthetic theory. Beyond her formalist leanings, Krauss states explicitly “October’s project has always been to bring European theory into the purview of American art practice because we really felt that a lot of things were incredibly relevant.”

Michelson’s background is in cinematic theory and film criticism, and much of her writing at October has covered issues at the intersection of film and art, particularly with the gloss of political concerns, such as when writing about Soviet Cinema, and in her editing of the collected writing of Japanese film director Nagisa Oshima, in Cinema, Censorship, and The State. Michelson’s writings have been considered particularly influential, generating a collection of essays in honor of her writing in 2003 called “Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida.” These essays reflect the various influences of Michelson on modern critics, from an interdisciplinary approach to art and film, to direct engagement with her writing. Like Krauss, Michelson has been particularly concerned with ideas of the avant-garde and modernism in art.

Over time, other critics such as Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin Buchloh, and Hal Foster joined Krauss and Michelson at October, among others. Bois brought with him in 1991 a distinct awareness of continental theory, as a result of his study under Roland Barthes in France. Originally from German, Buchloh studied under Rosalind Krauss, receiving his PhD from CUNY in 1994, though he’d already been writing at October for several years before. Foster was another student of Krauss’ who joined the editorial staff at October, continuing the magazine’s interest in the avant-garde and theory. In addition to the journal, Buchloh, Bois, Foster and Krauss have published together and independently, with texts suchs as Return of the Real (Foster), Art Since 1900 (Foster, Krauss, Bois, Buchloh), Neo-Avant Garde and the Culture Industry (Buchloh), and Painting as Model (Bois). Specific topics may differ for individual concerns, such as the anti-aesthetic for Foster, and Freudian “deferred action” or the materiality of surfaces and supports for painting and the specific nature of the culture industry, but in general, the critical concerns of the group center on modernism and post-modernism, and the historical trajectory of the avant-garde in art, and the manner in which art cycles with politics to reflect society.

These concerns have also woven through the text of the journal throughout its 36-year history. The very first issue in the spring of 1976 featured a translation of Michel Foucault’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” which addresses the Magritte image of the same name through theoretical concerns of semiotics, and then extrapolates that discussion to the larger concerns of Western Painting as a whole, addressing it in ways that directly engage with contemporary issues of art history and visual culture (see John Berger’s Ways of Seeing for his use of the image as well.) Of course, Foucault’s text exists within a French perspective, which has a distinctly different appearance than that of the German theorists of the Frankfurt School. Where the Frankfurt School concerns address the concerns of the political and the self through emancipation and enlightenment, the Foucault and others in the so-called French perspective are classed as Post-Structuralists. In order to properly analyze the trajectory of the journal in terms of the concept of Critical Theory both capitalized and not, I searched the entire catalog of October for keywords Frankfurt School, Critical Theory, and Adorno, which occur 54 times, 61 times, and 172 times, respectively, excluding front and back matter. By comparison, despite the sense that the journal might actually be more directly engaged with the post-structuralist approach, that term only applies to 9 citations in the journal’s 36-year history. I then broke down the mentions by years, trying to establish a pattern. Overwhelmingly, the years between 1988 and 1992 had the most significant presence of all three key words and topics, followed by 2000 through 2004.

In considering the role of the journal in response to politics and critical theory, these year groups could point toward a greater role of the concepts of human rights, pure democracy and other Frankfurt School concerns. With the breakdown of the Soviet Union, US involvement in the Cold War, and the fall of the Berlin Wall, in the late 80’s and early 90’s, and then the political upheaval and war in George W. Bush’s first term between 2000 and 2004, politics and personal liberty played a large role in almost all critical discussions at this time.

These overlapping years also feature special issue topics such as German film director Alexander Kluge, who was a friend and associate of Adorno, and “Humanities as Social Technology”, which could explain the higher marks in the years 1989 and 1990. The years of 2000 to 2004 have less clear an explanation through the titles and topics of the issues, other than a pervasive presence of conversations around the aura of images. Those years dealt with an extreme amount of imagery and issues regarding truth and politics of representation, from the instant and repetitive replay of the attacks on 9/11, to the photographs of prisoner abuse at the Iraqi prison Abu Ghraib, to the fabricated “Mission Accomplished” press conference President Bush held on an aircraft carrier regarding the military strikes on Iraq. It is easy to see where the theories of Benjamin, Adorno, and other Germans would come into consideration within the cultural boundaries of October.

The special issue of October in 1988 dealing with Alexander Kluge directly addresses the Frankfurt School through multiple paths, including a reprint of selections from Kluge’s Public Sphere and Experience, written with Oskar Negt, and translated by Peter Labanyi. The excepts address the exclusion of business and family association in the contemporary concept of the public sphere within bourgeois society, as well as other points of concern initially addressed in Jürgen Habermas’s The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Yet in the same year, Jonathan Crary’s “Techniques of the Observer” addresses the phenomenological in film and photography. In doing so, he moves back through Walter Benjamin (whose work is in alignment with the Frankfurt School in many ways) to Hegel and Goethe. While still addressing German modes of thought, Crary is writing more about experience of technology rather than its impact on society in a way that would reflect the Frankfurt School’s approach. The following year, Tania Modlewski wrote on the influence of continental (French) theory on feminist criticism, Sartre, and the body in “Functions of Feminist Criticism, or The Scandal of the Mute Body.” By fast forwarding to the 2000’s, the concerns in October change in a subtle manner. Still writing about art, the authors are less addressing the reader with a challenge of theory and avant-garde positions, but rather a more thoughtful view inward. Consider Mark M. Anderson’s writing about the late German writer and ex-pat W. G. Sebald. Anderson reads Sebald through the concerns of the Frankfurt School and Walter Benjamin, especially with regard to Sebald’s use of the image in the text. However, there is no denying the connection to the French approach and Roland Barthes’ “punctum,” also mentioned in the analysis. By this point in the 21st century, the journal seems less concerned with directly addressing the application of critical theory to art works and writing, and instead appears to take for granted the presence of theory in the various works, and knowledge of theory for the reader.

In 2002, Peter Muir wrote an article about October, Rosalind Krauss, and the Foucault essay mentioned earlier. In “October: La Glace sans tain” (the one-way glass, or “the mirror without silvering”), Muir addresses the Foucault essay within the trajectory of the journal as a “de-formative critical practice.” His analysis points to the long standing history of the journal as concerned with the work as text, and working in a manner of critical activism. He presents quotes from interviews with Krauss that frames the environment within which October was born and developed, a world in which there were “more vehicles…for neo-conservative positions, but for liberal and left wing there was less and less…” This attention to the politics and the way they operated within the art world is then one of the founding ideals of the journal. The other, through the selection of the Foucault text as the initial work in the first issue, is the linguistic turn, the address of the work as text, and critical theory, both in the broad forms established at the beginning of this essay, and the more strictly defined Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School.

The approach of left-wing radical liberalism, constructivist “anti-formalism”, and continental theoretical models of October influenced other theoretical journals, from Grey Room, also published by MIT Press, to the web journal Nonsite.org. Grey Room is in its twelfth year of publication, and the thrust of the journal mirrors much of the political and critical aspects of October, but with much less of an active regard for the place of modernism in art. Grey Room has followed the formal structure of October, from the quarterly peer reviewed issues, to special topic issues, to the critical approach that centers on art, architecture, media and politics, with an “emphasis on aesthetic practice and historical and theoretical discourse”. The theoretical origin of Grey Room is less steeped in French theory than October, which may be more a result of a shift in the cultural presence of critical theory as a specific discourse outside of the generalized concerns of social, political, and identity based framing of concerns. However, in 2007 the journal published an issue specifically focused on German Media Theory. In a direct comparison, Adorno is mentioned in the forty-nine issues of Grey Room 47 times (47 different articles), where Barthes is mentioned half that many. The idea that Critical Theory is a non-issue, approached as just previous knowledge gained from academic predecessors is further substantiated by the theoretical references in the footnotes of Grey Room articles, drawing on authors such as bell hooks, Judith Butler, Susan Sontag, and the various editors of October, including Michelson, Foster, and others, even when writing specifically about Roland Barthes.

Nonsite.org directly addresses their political position on neo-liberalism, and present their goal as the creation of a humanities think-tank whose “goal is to criticize what is and replace it with what we think ought to be.” The journal features scholarship in the humanities (beyond just art history) plus reviews, visual art, poetry and other features that are not present in either October or Grey Room. Nonsite.org is also published completely online, and includes a space called “The Tank” for engagement with new and provocative scholarship. Upon my visit to this space, the first article for engagement was titled “Do We Need Adorno?” Nonsite.org has a much shorter history for analysis, with only seven issues released to date. The current issue tackles Formalism and Post-Formalism (a topic that would not be out of place in October) and includes an article by Berkeley’s Whitney Davis, on the topic. Other issues also present a strong bias toward articles that would fit within any journal of art history or visual culture studies, including one that directly engages with the writings of Marx, Adorno, and the artwork as capital.

When considering the impact, then, of critical theory on art history through the written text of these journals, one must ask – how has art history changed? And has that change been art history itself, or are there social pressures being exerted on the field? October, as a journal, has been critiqued for its decision to be an art journal that elevates the primacy of the text, such as in Bernard Ortiz Campo’s article “Criticism and Experience” in E-Flux Journal. This decision includes the choice to limit image reproductions to black and white, which has garnered accusations of conservative, nostalgic taste. Grey Room has the same aesthetic, and reflects the importance of the text, which clearly defines their theoretical lineage. Nonsite.org appears to be responding to both journals, as well as the general nature of interdisciplinary concerns in academia, by creating what I would term a “post-theoretical” dialogue.

Art critics and art historians hold two very different positions to the artwork in traditional media. Historically, the critic is seen as one who writes about the work, championing its value, and presenting to the public knowledge about the artwork. Clement Greenberg, the major promoter and critic of Modernism, championed modernism over kitsch and cool analysis over emotional sentimentality. Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson came from the world of academia, despite their work at Artforum, and always laced their expositions with critical analysis, footnotes, cross-references, and essentially, the academic approach. To consider the work of October as work of the critic is to underestimate the journal’s position in art history. Art history came to the process of literary analysis and the work as text much later than other fields, and still has proponents who argue for the primacy of the object in art historical analysis. However, as can be seen in the transition from the field of traditional art history to visual culture studies, the influx of other fields, including the political and social bent of critical theory, has expanded the field of art history to involve greater concerns than merely the object. As Jae Emerling writes in the afterword to the 2005 Theory for Art History: “What is art history’s object of study? Is it art? …a subject?” In the post-structuralist world that has engaged with theory through October, Grey Space, May 1968 and Derrida, the field of art history has attempted to reckon with Walter Benjamin’s call for “an ethical and aesthetic critique”, and an awareness of the political implications of the artwork. To return to the Foucault article that October opened with, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” – the intersection between the word (text/theory) and the image (artwork) forms “an uncertain foggy region” and the “very absence of space.” It is in this space that art history finds itself, working through the legacy of critical theory as less a concern of the avant-garde, and more a legacy of looking through the violence of capitalism and idealism in the 21st century.

Adorno, Theodor W. and Max Horkheimer. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Jephcott, Edmund, trans. Noerr, Gunzelin Schmid, ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2002

Anderson, Mark M. “The Edge of Darkness: On W. G. Sebald” October Vol 106, Autumn 2003, pp 102-121

Beckman, Karen. “Nothing to Say: The War on Terror and the Mad Photography of Roland Barthes” Grey Room Vol 34, Winter 2008 pp 104-134

Benjamin, Walter. On The Concept of History. Trans. Richmond, Dennis. Creative Commons reproduction online. URL http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/benjamin/1940/history.htm Accessed November 15, 2012

Brown, Nicholas. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Real Subsumption under Capital” Nonsite.org editorial March 13, 2012 URL http://nonsite.org/editorial/the-work-of-art-in-the-age-of-its-real-subsumption-under-capital Accessed November 23, 2012

Campo, Bernardo Ortiz. “Criticism and Experience” E-flux Journal, no 13, February 2010 URL: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/criticism-and-experience/ Accessed November 21, 2012

Crary, Jonathan. “Techniques of the Observer” October Vol 45, Summer 1988, pp 3-35

Cronan, Todd et. al. “Do We Need Adorno?” The Tank, Nonsite.org, September 17, 2012, URL: http://nonsite.org/feature/do-we-need-adorno Accessed November 21, 2012

Davis, Whitney. “What is Post-Formalism? (Or, Das Sehen an sich hat seine Kunstgeschichte)” Nonsite.org, no 7, October 11, 2012 URL http://nonsite.org/article/what-is-post-formalism-or-das-sehen-an-sich-hat-seine-kunstgeschichte Accessed November 21, 2012

Elkins, James and Michael Newman, eds. The State of Art Criticism. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008

Emerling, Jae. Theory for Art History. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2005

Finlayson, James Gordon. Habermas: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2005

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard. “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” October, Vol 1 Spring 1976 pp 6-21

Gilbert-Rolfe, Jeremy, Rosalind Krauss, and Annette Michelson. “About October” October Vol1, Spring 1976, pp 3-5

Gunning, Tom. “To Scan a Ghost: The Ontology of Mediated Vision” Grey Room Vol 26, Winter 2007, pp 94-127

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Burger, Thomas, transl. Cambridge: MIT Press 1991

Krauss, Rosalind E. October: The Second Decade, 1986-1996. n.p.: MIT Press, 1997. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed October 13, 2012).

______. “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” October, Vol 8, Spring 1979 pp 30-44

Koerner, Joseph Leo and Lisbet Rausing. “Value” Critical Terms for Art History, 2nd edition. Nelson, Robert S. and Richard Shiff, eds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2003 pp 419-434

Levin, Thomas Y. “Walter Benjamin and the Theory of Art History: An Introduction to ‘Rigorous Study of Art.” October 47 Winter (1988): 77-83.

Modlewski, Tania. “Some Functions of Feminist Criticism, or Scandal of the Mute Body” October, Vol 49 Summer 1989 pp 3-24

Muir, Peter. “October: La Glace sans tain” Cultural Values Vol 6, No 4, 2002 pp 419-441

Schwartz, Frederic J. Blind Spots: Critical Theory and the History of Art in Twentieth Century Germany. New Haven: Yale University Press 2005

October digital archive, JSTOR Coverage: 1976-2006 (Vols. 1-118) Links to External Content: 2007-2011 (Vol. 119 – Vol. 137) MIT Press URL: http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublication?journalCode=october Accessed Multiple dates October – November 2012

Grey Room digital archive, JSTOR Coverage: 2000-2006 (Nos. 1-25) Links to External Content: 2007-2011 (Nos. 26-44) MIT Press URL: http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublication?journalCode=greyroom Accessed Multiple dates November 2012

Lecture on Modern Paris presented to Art History 102 students at CU Boulder in 2012 and 2013.

In 2015, I had the opportunity to present a class on Cell Phone Photography through the Art Student’s League of Denver, at Montbello Library.

While the presentation had more verbal information, this is an example of the visual presentation associated with my seminars and lectures on photography.